Sir Winston Churchill is often credited with the phrase “never let a good crisis go to waste” – said to be uttered during post-war efforts in forming the United Nations. More recently Rahm Emanuel further expanded on the saying with “Never allow a good crisis go to waste. It’s an opportunity to do the things you once thought were impossible.”

A similar refrain has been uttered by university leaders across Canada, the UK, and Australia. Covid has presented an opportunity to challenge the status quo and achieve change across university campuses. The question is whether these changes are being made in ways that are sustainable.

The pandemic as a catalyst for making difficult decisions is the underlying theme of what we intend to cover over in this latest series of articles. We start with a focus on what it means for universities to make operational savings that can be sustained for the long-term.

Many institutions went into the pandemic expecting to be financially challenged. However, in many cases have been pleasantly surprised by better than expected results. Revenues remained stable (or grew) with strong enrolments from international and domestic sources. At the same time there were “forced” cost savings with campus shutdowns. It is broadly acknowledged however that both the cost savings and enrolments have some risk. Costs are expected to come back with return to campus and international recruitment continues to be a competitive market with many inherent risks depending on which market an institution is dependent upon.

Where we have seen universities make operational savings a priority (whether to save on total cost or to re-invest in more strategic areas) the right kind of data has been able to highlight whether the savings will be sustainable. But before we get to that let’s set the context by briefly exploring what unsustainable savings look like.

Path 1 (the unsustainable): This path is typically characterized by expecting an across the board budget reduction of a certain target percentage. This can be supported by the rationale to have “everyone share the load” for the difficult decisions. We know that this can often penalize units already operating efficiently and potentially leave savings on the table from units that are underperforming.

Even where more targeted cuts are made the next error is making resourcing reductions without any consideration for real service model redesign. In simple terms, can you truly expect the same (or more) work to be done by fewer people doing it the same way they have always done it?

In an academic setting this results in dissatisfaction with service levels if conscious process and role re-design did not take place to deliver the service at reduced resourcing. We have seen several examples in the UniForum program where institutions have made short term resourcing reductions only to see resourcing return and exceed where it original was within a few years. This often results from local units undertaking their own local hiring to fill gaps in service provision.

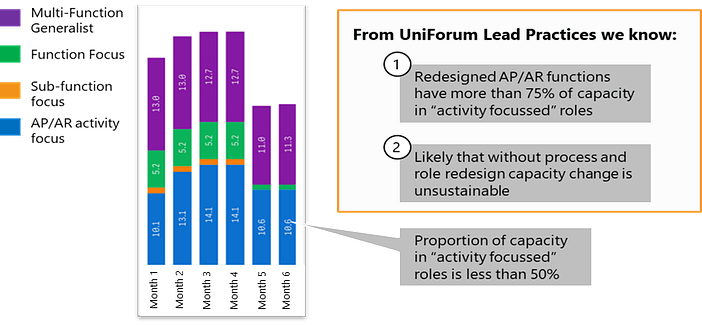

One specific example looks at an institution reducing spend in its accounts payable function. While the reduction took place, UniForum metrics highlight that this reduction was done without any accompanying operating model change. The data showed the process was distributed across the institution in much same way as before suggesting that processes have not been consolidated to drive scale and efficiency. Similarly, resource focus remains unchanged meaning that generalists are still largely responsible for the tasks.

Figure 1: UniX Professional Staff Resource Focus for Accounts Payable/Accounts Receivable

The data showed that accounts payable activity was already driven by “side of desk” effort. How could it be delivered sustainability within even fewer “sides of desks”? Likely not very effectively. Service users would be justified to look for ways to plug the gaps. In this context it’s no surprise to see costs steadily increasing once more.

Path 2 (sustainable change): By contrast, UniForum highlights what sustainable change can look like in the university context. Effective, long term change has been characterized by taking an end-to-end view of functions and processes, working across the borders of central service units, and academic departments.

This end-to-end view considers several key attributes of a process to support long term sustainability

Role design: has the process traditionally been dependent on fragmented support from many generalists across the university, each responsible for small parts of the process? Can this process benefit from consolidating the work to more focused roles, who with better training and tools can deliver the work more efficiently and effective by people with better training in the tools need to deliver the work efficiently and effectively?

Standardization and automation: Is there any strategic value to having customizations in the process for individual business units? Or does the process lend itself to being standardized and automated across the university?

Location of delivery / demand management: is the process or service best delivered from a central service centre which can triage demand from across the university and ensure equal service to all units regardless of size? Or is there value in having embedded resources which can understand the unique business needs of varying teaching and research areas?

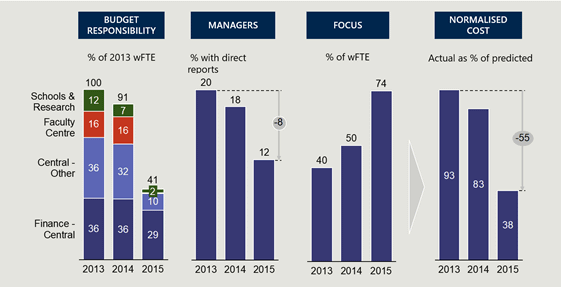

The graphic below shows how one university looked for the right levers to drive sustainable savings in Accounts Payable and Accounts Receivable. This institution understood that this transactional service made sense to be delivered centrally, with more focused resources, and wider spans of control.

There is no one single solution for all functions: these questions need to be answered on a process by process basis to create a model that is sustainable and works for the institution as a whole.

As in the example above UniForum data is a powerful tool to support the planning, implementation, and monitoring of a sustainable path to change. Some of the key insights UniForum data provides include:

Service delivery profile: how is service delivery organized across the university today?

This provides visibility to senior leadership of the end-to-end effort required to deliver administrative services, including effort centrally and in the Dean’s offices and departments

Role design: how are roles at the university structured to support the academic and teaching mission?

Unambiguous role data to understand whether roles are designed with a focus in specific activities and functions; or if there are high degrees of generalists tasked with supporting local units with a wide range of tasks

User experience: which service attributes have the greatest impact on the effectiveness of a service?

Data from the Service Effectiveness Assessment provides a view into the users’ experience and insight into which re-design lever is likely to have the greatest impact. For example, whether the solution to a service issue is system driven, training related, or relies on the point of delivery.

Combining this data, with direct access to 13 years of lessons learned from universities across the world enables universities to make the right design choices early on. The right choices compounded over time have proven to save 3-6% of revenue for re-investment into the core mission of teaching and research.

UniForum data, along with lessons learned from members is a powerful tool to help institutions plan, implement and monitor change programs to free up valuable resources to reinvest in the core mission of teaching and research.